11: Objects Humanity Has Thrown the Furthest

Voyager Mission — $865 Million

No other mission probably encompasses humanity’s desire for reaching out for the stars than the Voyager missions. It’s hard to believe now, but just a few decades ago we didn’t know much about the outer planets in our solar system. Grown out of the Mariner program, and just after the Apollo missions ended, the Voyager spacecrafts were meant to travel our Solar system and study outer planets in fascinating detail.

They took advantage of the planetary alignment of Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune that only happens once every 175 years. This alignment would allow for a single spacecraft to visit all of these four gas giants by using gravity assists from them. Dubbed as the Planetary Grand Tour, it was pitched as an opportunity to visit all of the outer planets in less time & with less money. No serious space program could pass up this once-in-a-lifetime opportunity.

Still this was no easy task when nobody knew how much fuel and what instruments might be required. There was also the big challenge of designing the spacecraft itself. The existing technology at the time did not have the same ‘processing power to size’ ratio advantage as today’s does. As predicted by Moore’s Law, I can type on my phone while listening to music, and running several apps in the background. Processing power was significantly more limited back then.

And yet, Voyager-2 launched on August 20 1977, from Cape Canaveral, Florida aboard a Titan-Centaur rocket. On September 5 1977, Voyager-1 launched, also from Cape Canaveral aboard another Titan-Centaur rocket.

Originally built to only last 5 years and mainly visit 2 planets, these spacecrafts were immensely successful in surpassing our wildest dreams. They followed the path NASA laid out for them to take advantage of planetary gravity assists, along with efficiently leveraging their nuclear power and clever reprogramming.

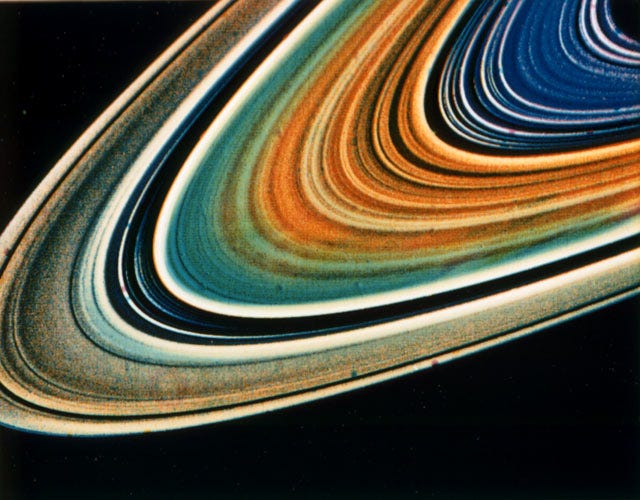

All this allowed the spacecrafts to get really close to their targets — Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, Neptune and several of their moons like Saturn’s largest moon Titan. Best of all, they observed various details that were previously unknown to us. Several new moons were found to be orbiting these planets, there was geological activity happening on these moons, these planets had outer rings and those rings were even more magnificent than previously thought.

Flybys of Jupiter in 1979 and Saturn in 1980/81 alone would have been successful enough to fulfill scientific curiosity and public demand. But we didn’t stop there.

By the time Voyager 2 got to Uranus in 1984, after visiting Saturn, the spacecraft showed sure signs of wear & tear. The primary receiver would not work. The backup would only partially work. Getting an image was already complicated due to Voyager’s speed of 30,000 miles an hour and the sunlight being 400 times dimmer than on Earth. Plus, Uranus is special in terms of its orientation — it actually rotates on its side. That means its moons are also at a 90 degree angle to the rest of the Solar System.

The Voyager missions again surpassed our expectations. We learned that the magnetic field was also odd that Uranus’s magnetic poles reside at the equator. A number of new moons and planetary rings were also discovered. One of the Moons, Miranda, turned out to be the star of the show with its complex & jagged surface.

Voyager 2 then continued to Neptune reaching it in 1989. A planet that is so far out that we had never taken a proper image of it before Voyager. Its orbit around the Sun, which takes 165 years, was mostly predicted by mathematical calculations. Neptune also only receives 3% light compared to Jupiter.

Needless to say, this was another monumental success for Voyager missions as fantastic new details about the last planet in our Solar system were discovered. Voyager found 6 new moons, finally solved the mystery of its ring (which were actually complete), and found that Neptune had the strongest winds in our solar system at about 1200 mph. Similar to Jupiter’s Great Red Spot, Neptune also had a large dark spot the size of Earth, which was dubbed the ‘Great Dark Spot’. Like Uranus, the magnetic field of Neptune also turned out to be highly tilted. Neptune’s moon, Triton, was the star of this show.

One of the big scientific achievements of the Voyager missions was to get us away from the thinking about a ‘goldilocks zone’ when looking for signs of life. For a while, we thought that unless a planet is in the habitable zone around its host star, it would not have life. Which makes sense because the energy needed to maintain a proper environment for life to thrive would come from the star. That was until Voyager missions returned new scientific data that forever changed our thinking.

From all the data coming back, everyone was surprised to find dynamic planetary systems. Like volcanoes on Jupiter’s Io, active geyser eruptions on Neptune’s Triton and atmosphere on Saturn’s Titan. These geological activities were due to strong tidal forces exerted by their gas giants. This discovery extended the range of the habitable zone and possible places to look for life in the universe. Every spacecraft and telescope that came after Voyager, including the JSWT, continues to refine our ability to search for life based on Voyagers’ success.

The amount of technological innovation this mission required, and the outsized effect it has had on our scientific progress, is certainly comparable to any other great human endeavors. Astonishingly, the story of Voyager spacecrafts doesn’t end here. More to come!